How Social Suport in Pakistani Families Impact Attachemnt of Couples

1. Introduction

All effectually the world, marital relationships are key and bones intimate bonds between 2 people. Beginning with the 2d half of the twentieth century, studies on matrimony focused on understanding the dynamics of marital performance that included satisfaction, violence and wellness hazards in relationships (Carvalho-Barreto et al. 2009). Numerous studies have examined the importance of religiosity (Aman et al. 2019) and self-compassion (Janjani et al. 2017), and its impact on marital relationships; yet, there are express studies (if whatever) carried out in Pakistan to understand the part of healing factors in marital quality (Hood et al. 2018); peculiarly when family violence ensues. Every bit a affair of fact, the less visible, simply about prevalent forms of violence are day-to-twenty-four hour period sufferings when violence festers in marriage. In developing countries, family violence has get a serious business organization for women and their health and their family's health. World Health Organization (1996) describes family violence as "… violent, threatening or other behavior by a person, men or women, that coerces or controls a member of the person'south family (the family member), or causes the family fellow member to exist fearful (pp. 5–6)". Cost of family violence includes physical and psychological health, relationship integrity, and quality of life, and since this matter in developing countries is culturally sensitive and private, researchers reluctantly and rarely probe or accost information technology, due east.g., in Pakistan, people are likely to maintain their positive paradigm, and express socially desirable responses most their lives and families (Henning et al. 2005), nonetheless 22% of women face physical abuse, 27% sexual violence, and lx% experience serious acts of psychological violence during their marital life (Zakar et al. 2012), compared to the charge per unit of the abuse of women in the US which is approximately 2 percent per year (Patricia and Nancy 1998). In another report, Khan et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis and reported that there is a charge per unit of 30–79% family violence in Pakistani households.

Family violence is a serious social and wellness problem due to its long-lasting harmful furnishings on women's health, wellbeing and relationships. If relationships are based on any kind of violence, it would ultimately compromise quality in the marital human relationship. Marital quality is a subjective evolution of the union and is a multidimensional construct associated with three dimensions: marital satisfaction, marital adjustment and relation with in-laws (Kousar and Khalid 2003). Poor marital quality was linked to mental health problems such as stress and low which may farther influence the full general quality of life (Karney and Nelson 1995).

Surprisingly, despite suffering, people often do not go out their spouses, and studies accept shown reasons for that include education, age differences, dowry, economic dependence, and societal pressure etc. (Koenig et al. 2003). Along with other factors that keep spouses together, compassion towards the spouse seems a skillful candidate, nonetheless pity towards ourselves may be diluted or absent, which could also touch marital relationships. Well-nigh of united states care for ourselves rather unkindly when bad things happen to united states in marriage, and rather than offering sympathy and support as we do to our loved ones, we tend to criticize ourselves, hide from others or ourselves in shame, and get stuck with ideas trying to make sense of what happened to united states of america. Such reactions and behaviors cause personal suffering and tin can influence interpersonal relationships. Studies report that when individuals see themselves as worthy and accept the ability to be happy and healthy, their power to maintain quality romantic relationships is preserved (Collins and Read 1990; Hazan and Shaver 1990; Mikulincer and Shaver 2003).

Fortunately, our hardwired capacity to respond to suffering in a soothing, healing manner is self-compassion (Neff 2011). Self-compassionate people have three components: cocky-kindness, a sense of mutual humanity, and mindfulness when confronting negative self-relevant thoughts and emotions. Self-compassion is truly the change of negativity about worst situations into positive thinking and reactions (Neff 2003b). Williams (2015) came up with the fact that cocky-compassion and self-forgiveness aid people to come up out of their shame and avoidant behaviors. Self-compassion is likewise linked with happiness and health of married couples which ultimately predict the quality of a relationship (Neff and Beretvas 2013).

Religion is however another significant protective factor for married couples to maintain their relationships. 1 of the central points in Islam is to maintain social and marital life, by asking followers to be nurturing when bonded in family life rather superficially holding marital obligations. Similarly, practicing religious activities similar praying, recitation of Quran etc. are linked with marital well-being (Alsharif et al. 2011).

It is reported that religious people are happier and more satisfied in their relationship (Stafford 2016) and have stable married lives compared to non-religious married couples (Langlais and Schwanz 2017). Similarly, Austin et al. (2018) written report, religious couples tend to view divorce negatively, and are willing to sacrifice for their spouses to maintain happy marriages. Religious delivery and religious practice strengthens and promotes marital satisfaction in couples living in urban areas (Aman et al. 2019).

In Pakistan, research in exploring protective factors of family violence is still in its embryonic phase, because this matter is culturally sensitive and individual and therefore victims are unlikely to share information or tell "outsiders" nigh their problems (Ayyub 2000). Family violence does non occur every bit an isolated incident in the lives of abused married women, rather it recurrently causes harm not only on the victims, but to their families and on society equally whole (Carvalho-Barreto et al. 2009). These untold stories of family violence ranging from psychological torture to physical violence tends to be harmful for physical and mental health of married adults and poison for their relationships further impeding their marital quality. Marital quality is an important and integral attribute of family life playing important function in the married adults' wellness and wellbeing. In Pakistani patriarchal club, unremarkably married adults have to continue calumniating relationships despite poor marital quality, due to some cultural and other reasons. Studies accept proved that married adults with calumniating partners utilize a variety of coping strategies to deal with family violence. A majority of women (97%) reported that spirituality or God and turning to their religion was a source of strength or comfort for them (Gillum et al. 2006). Another important factor was self-pity which protects people against stressful events and is very important for an individual's mental wellness (Allen and Leary 2010). These protective factors do non necessarily eliminate the stresses and strains only help to run across the trouble in a unlike context.

2. Hypotheses

Main objective of the present study was to analyze the influence of family violence on the marital quality of married Muslim adults living in Islamic republic of pakistan. Further, information technology was aimed to investigate the function of personal factors (i.e., religiosity and cocky-pity) in protecting confronting family violence and improving marital quality of married adults. Another objective was to explore gender differences in terms of these personal factors, marital quality and family violence. Based upon these objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated:

-

Religiosity is likely to moderate the relationship between family violence and marital quality of Muslim married adults of Pakistan.

-

Self-compassion is likely to mediate the human relationship between family unit violence and marital quality of Muslim married adults of Pakistan.

-

Significant gender difference would be institute in terms of religiosity, marital quality, self-compassion and family unit violence.

3. Conceptual Framework

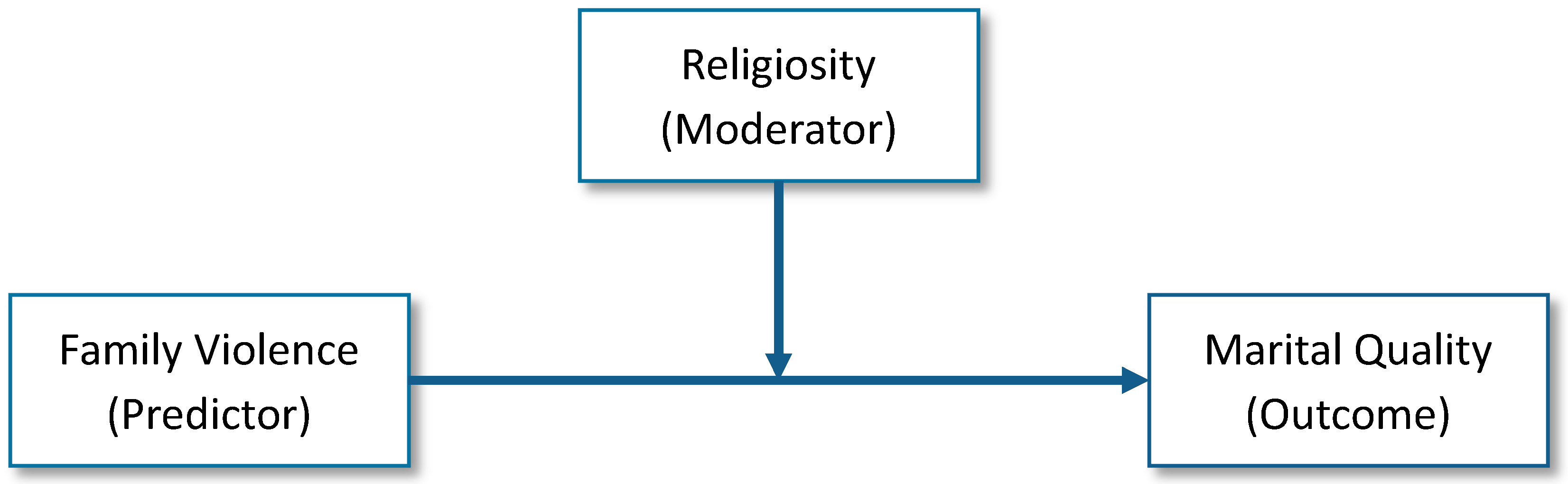

Hypothesisi.

Model (see Figure i).

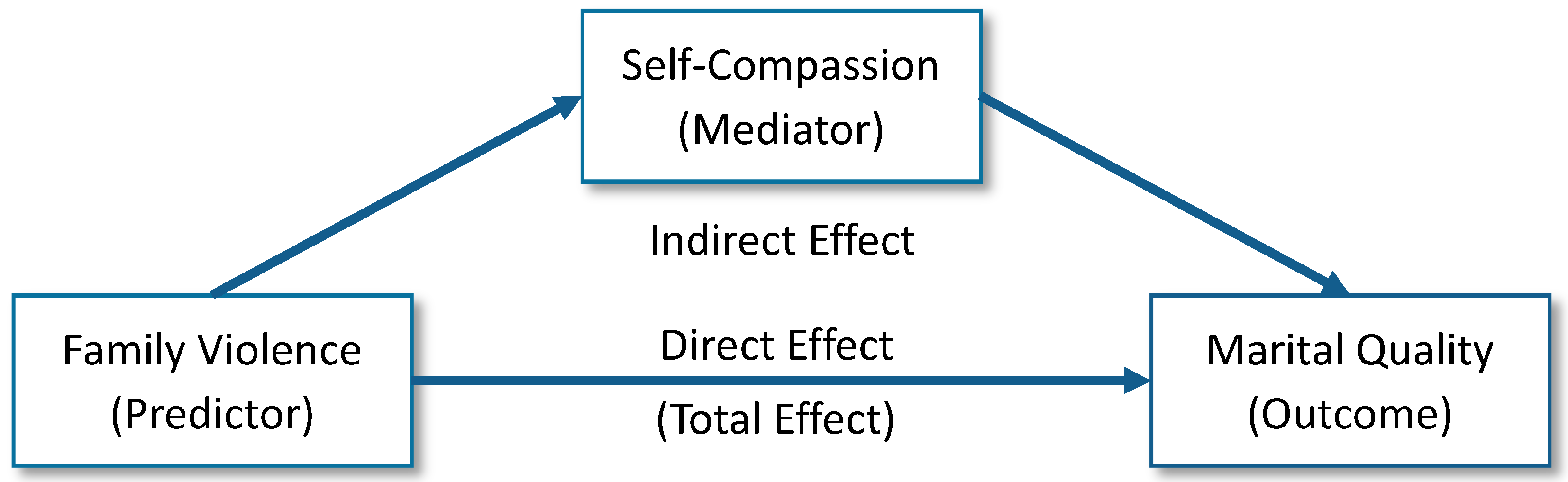

Hypothesis2.

Model (see Effigy 2).

4. Method

The present study was designed to examine the part of self-pity and religiosity in marital quality amidst married Pakistani Muslims in abusive or tearing relationships. Item of the sample, instruments and procedure is given below:

4.1. Participants

The present study consisted of a purposive sample of 262 (44%) married men and 338 (56%) women (due north = 600) recruited from various cities of the Punjab. Participants ages ranged from 19 to 51 years (Yard = 35.ninety, SD = seven.30), with a minimum of one yr of marriage. Since the sample was purposive, nosotros used those married adults who were facing some kind of family unit violence in their lives.

4.2. Instruments

Family unit Violence Scale (FVS). This is a family violence scale for married adults (Perveen and Malik 2019) a 37-item calibration where each item is rated on a v-bespeak Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). This scale is divided into five subscales, which include, 6-item Sexual Abuse subscale (e.chiliad., "I am forced to make those sexual acts which I don't like"), 10-item Social Degradation subscale (e.chiliad., "I am not allowed to run across people"), five-item Economical Assail subscale (due east.g., "My basic economical demand are not fulfilled "), 11-item Psychological Torture subscale (eastward.g., "I am insulted") and 5-particular Concrete Violence subscale (e.g., "I am dragged past pulling my arms"). Higher score on the calibration and subscales represent greater family violence. The internal consistency of the calibration measured (α = 0.96) previously (Perveen and Malik 2019) and obtained reliability is (α = 0.94) in this study (see Table 1).

Cocky-Compassion Questionnaire (SCS).Neff (2003a) developed a 26-item cocky-report questionnaire on cocky-compassion that rates each item on a 5-point Likert-blazon calibration ranging from 1 (Most Never) to 5 (Almost E'er). This calibration measures the extent to which people appoint in cocky-kindness versus cocky-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over identification through 5 subscales, which include, 5-item Cocky-Kindness subscale (e.thousand., "I endeavor to be understanding and patient toward aspects of my personality"), the v-item Self-Judgment subscale (eastward.g., "I'm disapproving and judgmental most my own flaws and inadequacies"), the 4-item Common Humanity subscale (east.g., "I try to see my failings as part of the human condition"), the four-detail Isolation subscale (e.one thousand., "When I call up about my inadequacies information technology tends to brand me feel more dissever and cut off from the rest of the globe"), the 4-particular Mindfulness subscale (e.grand., "When something painful happens I try to take a counterbalanced view of the state of affairs"), and the 4-item Over-Identification subscale (east.g., "When I'k feeling downward I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that's wrong."). The internal consistency was reported as α = 0.92, nevertheless obtained reliability coefficient in this study was α = 0.71 (meet Tabular array i).

Middle of Religiosity Questionnaire-15 (CRS-15). This is a measure of the "axis, importance or salience of religious meanings in personality" (Huber and Huber 2012) and is suitable for Abrahamic religions including Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The scale consists of fifteen items and divided into five subscales: intellect—iii items (due east.m., how ofttimes practise you lot think virtually religious issues?), ideology—3 items (e.1000., in your opinion, how likely is it that a higher power really exists), public practise—3 items (e.k., how ofttimes exercise you take part in religious services?), private practise—three items (How often exercise you pray?) and religious experience—three items (due east.g., how often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine is present?). In three studies reliabilities of CRS-15 ranged from 0.92 to 0.96 (Huber 2007) and for the electric current study (α = 0.75) run across Table i below.

Marital Relationship Questionnaire (MRQ).Kousar and Khalid (2003), developed MRQ based on Burgess Marriage Aligning Schedule (Burgess and Locke 1960), and it consisted of 48 items. The scale has three dimensions of marital relationship which collectively ascertain marital quality. These dimensions are comprised of 22 items of Marital Adjustment subscale (e.g., "can yous openly discuss your opinion with your hubby?"), 21 items of Marital Satisfaction subscale (e.1000., "do y'all think your marital life is happy life?), and 5 items of Human relationship with In-laws subscale (eastward.g., "do y'all help your in-laws in the fourth dimension of need?"). These three dimensions collectively decide the quality of marital relationship and higher score represents greater marital quality. Obtained reliability of the scale in this case was α = 0.84. Run across Table 1 below.

4.3. Procedure

Permission for information drove was sought from the departmental head and then from different Health Care Centers of selected cities. For reasons involving sensitivity of the topic, these centers were approached for obtaining access to participants who were facing some form of family violence. Those married adults who came to seek healthcare in these clinics were requested to provide information on the questionnaire after receiving their consent. This arroyo was particularly indispensable because approaching women who confront violence at home could not be sought at their residence for a number of reasons from living in joint families to strong patriarchal values that could have prevented u.s. from reaching them for testing. All participants were briefed near the report and confidentiality and anonymity of data was assured. A packet that consisted of demographic canvass and scales mentioned above were distributed to the participants. There was no restriction of time for the completion of scales. As a gesture of gratitude, at the individual level for some participants a "listening ear" was provided to counsel those, if such a request was made.

5. Results

Table i presents mean, standard deviations, reliabilities and inter-correlations of scales used in the study and indicates that scales had moderate to loftier internal consistencies. Results revealed pregnant (p < 0.01) negative correlations between family violence and religiosity and marital quality, but not with self-compassion. In addition, self-compassion and religiosity were significantly positively correlated (p < 0.01); self-compassion and marital quality were significantly (p < 0.01) positively related; and finally religiosity and marital quality were too significantly (p < 0.01) positively correlated.

Table two showed inter-correlations among scales and subscales. Religiosity and its subscales are negatively and significantly (p < 0.01) associated with family unit violence and with all its subscales. Findings revealed that religiosity has positive and significant correlation with all other scales and subscales used in the report except two subscales. These public practise and individual practice subscales of religiosity have a positive but non-significant correlation with the cocky-judgment scale of cocky-compassion. Self-pity has a negative relationship with social degradation and economical assault subscale only it has positive and meaning (p < 0.01) correlation with physical violence. It has negative but not-significant correlation with the total scale of family unit violence. Furthermore, self-pity is positively associated with religiosity and marital quality. Reliabilities of all scales and subscales showed moderate to high internal consistency ranging from 0.69 to 0.94.

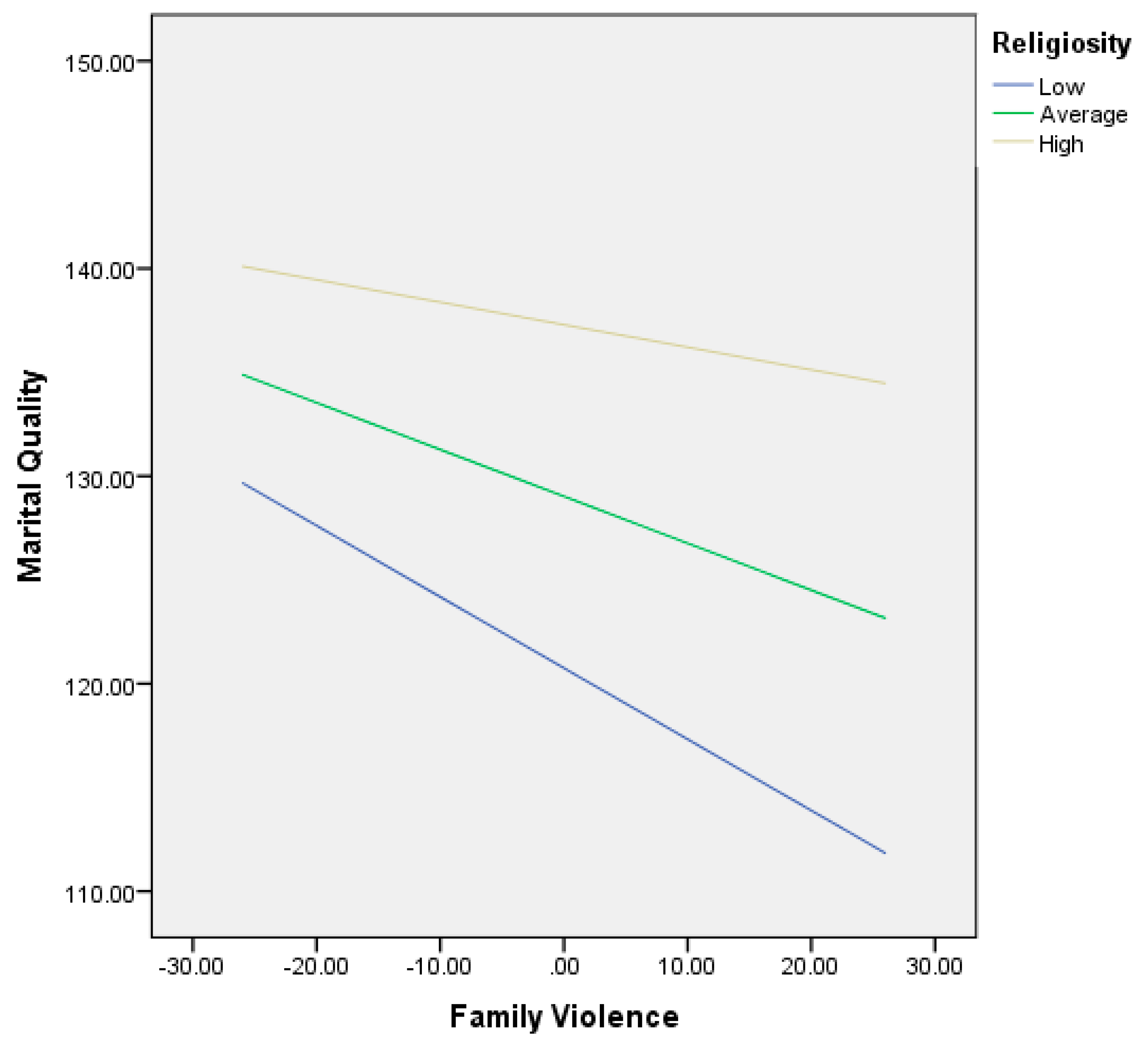

Moderation analysis was carried out with Process macro for SPSS (Hayes 2018). Results in Table 3 showed religiosity played a moderating role between family unit violence and marital quality among Pakistani Muslim married adults. The value of R² indicates a 26% of variance in the outcome variable is explained by the predictor with F (iii, 596) = 69.97, p < 0.001. The value of ∆R 2 is 0.01 with ∆F (one, 596) = 10.45, p < 0.001 which explains variance of one% by the boosted effect of religiosity. The findings revealed that religiosity (B = ane.02, p < 0.001) is positively associated with marital quality while interaction effect of family violence and religiosity (B = 0.01, p < 0.001) has significant buffering consequence on marital quality. This indicates that the higher the religiosity, the weaker is the negative effect of family violence on marital quality.

Effigy 3 indicated conditional effects of iii levels of religiosity which were negative and meaning (at −1SD, b = −0.34, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001; at mean, b = −0.23, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001; at +1SD, b = −0.11, SE = 0.05, p < 0.02). The gradient showed that married adults who reported a high level of religiosity maintained their quality of marital relationship despite of facing unlike kinds of family unit violence. Individuals with a college level of religiosity had higher scores of marital quality beyond all levels of family violence in comparison to individuals with depression levels of religiosity. Religiosity proved equally a protective factor buffering the negative consequences of family violence by weakening or diminishing the negative association between family violence and marital quality.

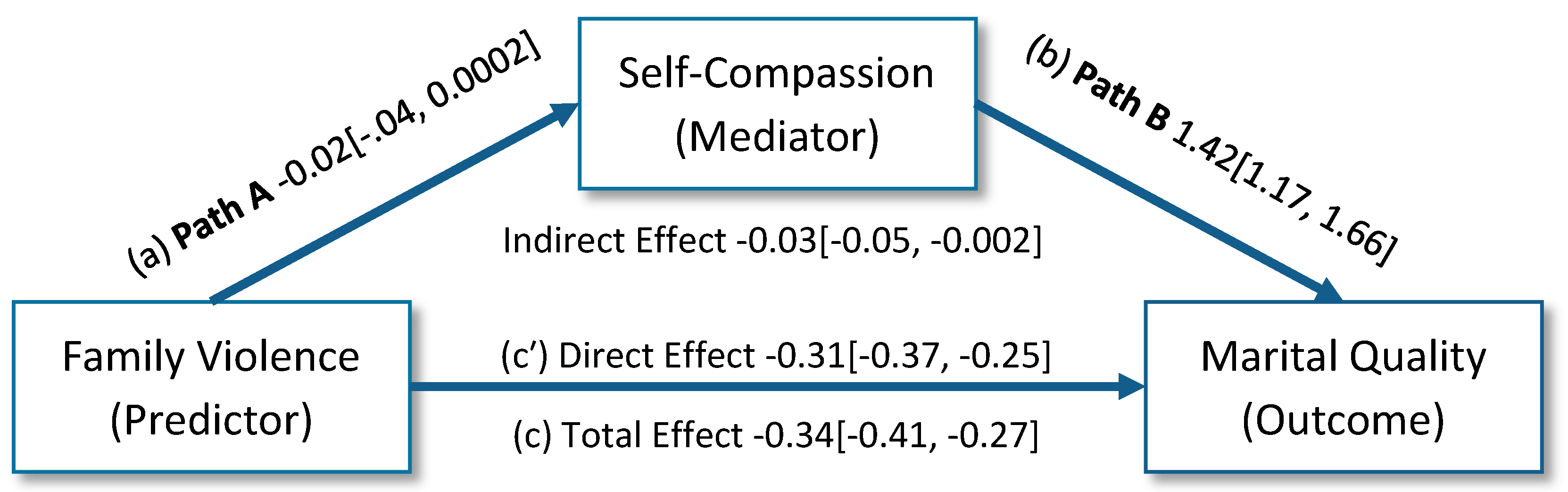

Mediation analysis was carried out with Process macro for SPSS (Hayes 2018). Table four showed total, directly, indirect and partial arbitration effect of family violence on marital quality of Muslim married adults. R2 value of 0.01 indicates that self-compassion explained 1% of variance in marital quality with F (1, 597) = three.78, p < 0.001. R2 value of 0.29 indicates that 29% of variance in marital quality is explained past both self-pity and family violence with F (1, 597) = 122.45, p < 0.001 while full R2 of the model explains 14% of variation with F (1, 597) = 99.31, p < 0.001.

Full effect emerged as statistically significant with, t (600) = −9.97, p = 0.001 or between −0.40 and −0.27 with 95% confidence interval. Direct effect was statistically different from zero, t (600) = −ten.03, p = 0.001 with a 95% confidence interval from −0.37 to −0.25. The straight outcome of family violence c′ = −0.31, is the estimated divergence in marital quality between two married adults experiencing the aforementioned level of self-pity only who differ past ane unit in their reported family violence. The coefficient is negative, meaning that the person who is facing a higher level of family unit violence but who as uses the aforementioned level of sell-pity is estimated to exist 0.31 units lower in his/her reported marital quality. (see Figure 4).

Findings revealed that the indirect effect (b = −0.03) is statistically different from zero (−0.05 to −0.001), as revealed past 95% bootstrap confidence internal that is entirely in a higher place zippo. This showed that ii married adults, who differ by ane unit of measurement in facing family violence, are estimated to differ past 0.03 units (iii%) in their reported marital quality as a outcome of more self-compassion, which in turn translated into greater marital quality (because b is positive). This indirect upshot confirmed the fractional mediating effect of self-compassion in relation to family unit violence and marital quality of Muslim married adults. To put it but, negative consequences of family violence were reduced when married adults were engaged more in self-compassion. The statistical diagram of mediation is presented below along with significant path coefficients

Results of Tabular array 5 indicated meaning gender differences in terms of religiosity F(one, 559) = 8.57, p < 0.01, marital quality F(i, 559) = 30.99, p < 0.001, and family unit violence F(1, 559) = 121.41, p < 0.001. Furthermore, additional results of mean values revealed that men were more than religious (K = 57.77, SD = 7.62) as compared to married women (Thou = 55.fourscore, SD = 8.30) and men (Chiliad = 134.33, SD = 23.12) also scored high on marital quality as compared to women (G = 123.63, SD = 22.83). Married women (M = 77.77, SD = 27.25) were facing more family violence as compared to men counterparts (M = 99.70, SD = 21.21). Moreover, at that place were no pregnant effects of gender regarding the use of self-compassion indicating that ratings from men and women participants were in general the same. Moreover, values of Partial Eta Square revealed that seven% of all variance in religiosity (ηii = 0.07), 15% variance in marital quality (η2 = 0.xv) and 17% of all variance in family violence (ηii = 0.17) was deemed for by gender. Furthermore, values of observed power of all these variables showed from 83% to 100% probability for finding significant results.

6. Give-and-take

The present written report examined the office of religiosity and self-compassion as moderating and mediating betwixt family violence and marital quality in Pakistani married Muslims. Findings supported our first hypothesis that a negative relationship existed between family violence and marital quality (see Figure ane). Family violence is a serious health and emotional problem, which impedes the quality of life and life satisfaction (Cattaneo and Chapman 2013). Our results are aligned with Razera et al. (2016) who report violence in the marital relationship is associated with lower level of marital quality. The fact is, when a partner is mentally or physically tortured past his or her spouse so the overall appraisal of contentment with his or her marriage is severely affected and this overall appraisal of contentment with the human relationship is the marital satisfaction which is the of import component of marital quality (Kamp Dush et al. 2008, p. 212). It is also noted that, victims of family violence may develop mental health problems too, such equally emotional distress, depression and anxiety (Ellsberg et al. 2008), which further leads to dissatisfaction of relationship with spouses and impedes marital quality.

Results supported our hypothesis regarding the moderating part of religiosity between family violence and marital quality. Previous researchers confirmed our findings that religious values and religious attendance have positive associations with spousal commitment and marriage; hence leading to a quality relationship (Scot et al. 2008). Inclined towards organized religion, makes someone to forgive others for the sake of God and this attitude ultimately helps them to maintain their level of satisfaction in calumniating relationships (Stafford 2016). For many believers, religion is not simply a belief system simply a code of life dominating personal and social life (David and Stafford 2013). In Islam, husband and wife both are supposed to baby-sit each other'due south rights, equally Al-Quran, allegorically says "They are vesture for you and you are habiliment for them" (Qur'an 2:187). A husband is given a status of the "governor of the house" and a woman is guided to obey him and take care of the dwelling house. If he mistreats her, she is religiously guided to evidence patience to save the human relationship and vice versa. Researchers institute a positive effect of religiosity for marital quality promoting psychological wellbeing for survivors of family unit violence (Gillum et al. 2006), and women who attended a greater number of religious services were less probable to get divorced (Dark-brown et al. 2008). Studies have as well shown couples who had religiously involved spouses generally had significant positive impacts on various aspects of union and family life, such equally marital quality, forgiveness, psychological wellbeing, self-esteem, life satisfaction and longevity (Marks 2005). Information technology was also found that spouses who pray for each other and attend religious services together seem to experience amend marital quality (Ellison et al. 2010).

Another hypothesis was as well supported suggesting that self-compassion mediates the relationship between family violence and marital quality (see Figure 2), and weakens the relationship. In other words, negative consequences of family violence were reduced when at that place were high levels of self-pity thus protecting marital quality. Protective factors exercise not necessarily eliminate the stressful events, rather they buffer impacts of stressful events, altering or reverting ascension of negative furnishings (Masten et al. 2009).

Neff and Beretvas (2013) reported cocky-pity as a good predictor of marital satisfaction amid married couples. These researchers constitute that 85% of people reported suffering some form of domestic violence but when the quality and violence variables were examined separately, most couples (~67%) evaluated their relationship every bit boilerplate to very good because of self-compassion. Specifically, self-compassion has been found to be related to happiness, college level of life-satisfaction and better emotional regulation (Barnard and Curry 2011).

The central concept of cocky-compassion would be to treat oneself well in times of difficulty (Neff 2003a); which is important peculiarly for victims because usually they come across themselves every bit the reason for any kind of violence faced at home. This helps them to lessen suffering, through patience, kindness, and understanding and recognize that all humans are imperfect and make mistakes. When we are mindful of our suffering and answer with kindness, remembering that suffering is a role of the shared human being condition, we are able to cope with life'southward struggles and worse situations with greater ease (Neff et al. 2005).

Findings of the study showed gender differences in terms of religiosity, marital quality, and family violence while men and women were non different in the apply of self-pity. Findings showed that married women were facing more than family unit violence as compared to married men. Literature supported our findings as 48 population-based studies from different parts of the earth revealed the fact that ten% to 69% of the women reported having been physically attacked by their spouse during their lifetime (Krug et al. 2002). In Islamic republic of pakistan, the rate reported by married women during their live for physical violence was 32%, 77% for sexual abuse and 90% for psychological abuse (Ali et al. 2015). In patriarchal society, women experience partner violence and continue their abusive human relationship because of their adherence to patriarchal norms and worse consequences. They often understood their situation as just part of the pain of being in a committed relationship and overlook the intensity of the state of affairs to stay in this abusive human relationship (Hayes 2014).

Gender differences were establish in terms of marital quality. Mean values revealed that men were enjoying marital quality every bit compared to married women. In this collectivist civilisation, women are supposed to fulfill all the duties of family members including in-laws. Nonetheless, despite all day working hard, she is non acknowledged for her time and efforts fifty-fifty by her husband and is taken for granted. She could non get along with and enjoy the visitor of the marital partner. This lack of pleasance and feelings of worthlessness reduces her marital quality. While on the other hand, in this male dominated society, men perceive themselves as superior and they think earning is their only duty. Equally they are fulfilling the bones needs of the wife, which is their only responsibleness, they might experience more adjusted as compare to their counterparts. Bradbury et al. (2000) have supported our findings by arguing that quality of relationship is related to the capability for accomplishing daily demands and duties of marriage. Another study (Ackerman 2012) supported our findings by confirming that men tin can maintain quality of their marital relationship relatively hands every bit it would be easier for them to maintain loving relationship with aggressive women but for a women it is very difficult to alive with an abusive husband. Similarly, equally in a collectivistic society, men are given more than privilege as a "son in-law" every bit they go more than respect and social approving of the relationship from in laws every bit compared to married women (Marks et al. 2001). In Pakistani cultural context, blurred boundaries between the relationship with in-laws and spouses play an influencing function that may affects the quality of marital interactions between spouses.

Results revealed that married men were more religious than married women. Our findings were contrary to some of the previous research equally in U.s. and in many other countries, women were intended to be more religious than men (Baker and Whitehead 2016; Schnabel 2016) and even some religious scholars have argued that women may be biologically predisposed to be more religious (Beit-Hallahmi 2014; Stark 2002). Past contrast, in Muslim-majority countries gender gaps are less consistent equally Muslim men are more likely to attend religious services than Muslim women in keeping with Islamic norms (Hackett et al. 2016). This religious involvement might be the reason that all married male participants continued their dissatisfactory marital relationship. Although religious participation does non seem to directly reduce problems of union life, a strong religious belief in marriage as a lifetime commitment has been linked to greater marital quality and stability (Heaton and Albrecht 1991). The fact is, the true spirit of the Islamic religion provides back up and nurturance for patterns of family unit life instead of merely focusing on traditional concepts of marital obligations. Similarly, performing religious activities like praying, recitation of Quran etc. is linked with marital satisfaction and is considered as i of the good coping strategies (Alsharif et al. 2011). Being more inclined towards religion and ascribing greater importance to religion in someone'due south life, makes someone forgive others for the sake of God, and this attitude ultimately helps them to maintain their adjustment and quality in abusive relationship (Stafford 2016). These results are likewise supporting our previous findings concerning why men scored high on marital quality as compared to women.

As far as cocky-compassion is concerned, no significant gender differences were institute. Married men and women both were using the same level of cocky-compassion to deal with abusive relationships. Researchers found that every bit cocky-compassionate people accept themselves every bit imperfect individuals, this helps them to be more inclined to accept their partner's limitations and ignore their trigger-happy behaviors (Van Dam et al. 2011). Both married adults used self-pity every bit a coping strategy to handle relationship issues demonstrating that this factor is a source of forcefulness in times of struggle, which helps people cope with stress in a more than powerful manner (Allen and Leary 2010).

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations

This evidence-based report suggests the healing effect of personal factors in married adults' life especially when facing different kinds of family violence. However, there may exist few possible limitations of the study that should exist interpreted with caution. The present report is correlational and may limit causality amidst variables. Furthermore, this written report employed self-report measures, which might be susceptible to social desirability bias. Participants in our study were recruited from one province of Pakistan, for future research all provinces and territories should be included to extend generalizability of the nowadays findings. For time to come studies, it would be more worthwhile to use a mixed-methods approach and experimental pattern as information technology would requite a detailed movie of family violence and marital quality. In spite of these limitations, findings of the study added significant information to the growing trunk of knowledge nearly family unit violence. It also provides valuable guidance for the professionals to design interventions aimed at reducing the risk of family violence and increasing marital quality of Muslim married adults. Based on research findings, the following policy recommendations are suggested in order to control family unit violence against married adults:

-

To eradicate the problem from the root, ane of the most important considerations is to modify male person-dominant ideologies which needs national level educational reforms. It is recommended to revise educational curriculums to make them gender sensitive and discourage bigotry. Furthermore, to reduce the run a risk of family violence on short term basis, there should be enough educational programs, both for women and men at the same levels.

-

Media should be warned to play a responsible role in terms of the aired content especially on family channels. Concerned authorities should intervene to promote women's office as leaders and equally respectable components of the society instead of portraying them every bit victims of violence. All electronic and print media should alter the way they portray women.

-

All health professionals should exist trained regarding this sensitive issue and authorities should have crisis centers and martial counseling centers in primary health care centers like rural health centers, and main ceremonious hospitals throughout the state.

-

Mental health practitioners might play an of import part in designing culturally relevant interventions in clinical settings for married adults. In improver, Muslim scholars could play a strong office in nurturing the spiritual lives and improving the quality of the marital relationships for married adults when they seek spiritual counseling.

-

Although women are already working, the need to ensure more women are involved in formal services (such equally police forces and courts of justice) and to adapt extensive training nearly the sensitivity of the topic for police force officers to remove an of import bulwark to justice for victims of family violence.

-

Based upon observation, researcher would also highly suggest the Authorities of Pakistan to develop some recreational programs (specially in pocket-sized town and cities) including family unit parks, and other entertaining places where women forth with their family can enjoy and relax.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P and S.Yard.; methodology, A.P and S.M.; software, A.P.; validation, A.P and Southward.Grand.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, A.P and S.M.; resource, A.P.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, AP.; writing—review and editing, A.P and Due south.M visualization, A.P and S.M.; supervision, S.K.; projection administration, A.P and S.Grand. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This inquiry received no extra funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of interest.

References

- Ackerman, Jeffrey M. 2012. The relevance of relationship satisfaction and continuation to the gender symmetry debate. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27: 3579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Parveen Azam, Paul B. Naylor, Elizabeth Croot, and Alicia O'Cathain. 2015. Intimate Partner Violence in Pakistan: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Corruption sixteen: 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, Ashley Batts, and Mark R. Leary. 2010. Self-Compassion, Stress, and Coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharif, Naseer Z., Kimberly A. Galt, and Ted A. Kasha. 2011. Health and healing practices for the Muslim community in Omaha, Nebraska. Journal of Religion & Society seven: 150–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, Jaffar, Jaffar Abbas, and Shaher Bano Nurunnabi. 2019. The Human relationship of Religiosity and Marital Satisfaction: The Part of Religious Commitment and Practices on Marital Satisfaction among Pakistani Respondents. Behavioral Sciences ix: xxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Philip, Jessica Macdonald, and Roderick MacLeod. 2018. Measuring Spirituality and Religiosity in Clinical Settings: A Scoping Review of Bachelor Instruments. Religions 9: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyub, Ruksana. 2000. Domestic Violence in the South Asian Muslim Immigrant Population in the U.s.. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless 9: 237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Josheph O., and Andrew 50. Whitehead. 2016. Gendering (non)organized religion: Politics, teaching, and gender gaps in secularity in the United States. Social Forces 94: 1623–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Laura K., and John F. Curry. 2011. Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology fifteen: 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. 2014. Psychological Perspectives on Religion and Religiosity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, Thomas N., Frank D. Fincham, and Steven R. H. Beach. 2000. Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family 62: 964–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dark-brown, Edna, Terri L. Orbuch, and Jose A. Bauermeister. 2008. Religiosity and marital stability among black American and white American couples. Family unit Relations 57: 186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Eaarnest Watson, and Harvey J. Locke. 1960. The Family: From Establishment to Companionship, second ed. New York: American Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Barret, André de, Júlia Sursis Nobre Ferro Bucher-Maluschke, Paulo César de Almeida, and Eros DeSouza. 2009. Human evolution and gender violence: A bioecological integration. Psicologia Reflexão due east Crítica 22: 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, Lauren B., and R. Aliya Chapman. 2013. American Muslim Marital Quality: A Preliminary Investigation. Journal of Muslim Mental Health seven: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Nancy L., and Stephen J. Read. 1990. Adult attachment, working models, and human relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58: 644–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, Prabu, and Laura A. Stafford. 2013. Relational Approach to Religion and Spirituality in Spousal relationship: The Part of Couples' Religious Communication in Marital Satisfaction. Periodical of Family Issues 36: 232–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher Grand., Amy Grand. Burdette, and W. Bradford Wilcox. 2010. The couple that prays together: Race and ethnicity, religion, and relationship quality among working-age adults. Journal of Marriage and Family unit 7: 963–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, Mary, Henrica A. Jansen, Lori Heise, and Charlotte H. Watts. 2008. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental wellness in the WHO multi-land study on women'southward health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet 371: 1165–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillum, Tameka Fifty., Cris M. Sullivan, and Deborah L. Bybee. 2006. The importance of spirituality in the lives of domestic violence survivors. Violence confronting Women 12: 240–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Conrad, Caryle Murphy, David McClendon, and Anne Fengyan Shi. 2016. The Gender Gap in Faith around the World: Women Are Mostly More Religious than Men, Particularly among Christians. Washington, DC: Pew Enquiry Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Sharon. 2014. Sex, Honey and Abuse: Discourses on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Arbitration, Moderation, and Conditional Procedure Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, Cindy, and Phillip R. Shaver. 1990. Love and work: An attachment theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 270–lxxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, Tim B., and Stan 50. Albrecht. 1991. Stable Unhappy Marriages. Journal of Matrimony and the Family 53: 747–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, Kris, Angela R. Jones, and Robert Holdford. 2005. "I didn't do information technology, but if I did I had a expert reason": minimization, deprival, and attributions of arraign among male person and female person domestic violence offenders. Journal of Family Violence twenty: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Ralph R.Due west., Peter C. Loma, and Bernard Spilka. 2018. The Psychology of Organized religion: An Empirical Arroyo. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are religious beliefs relevant in daily life? In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Edited by Heinz Streib. Lieden: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Calibration (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjani, Parisa, Lida Haghnazari, Farahnaz Keshavarzi, and Alireza Rai. 2017. The role of self-compassion factors in predicting the marital satisfaction of staff at Kermanshah University of medical sciences. Earth Family Medicine/Middle E Journal of Family Medicine fifteen: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, Dush Claire G., Miles Thou. Taylor, and Rhiannon A. Kroeger. 2008. Marital Happiness and Psychological Well-Beingness beyond the Life Course. Family unit Relation 57: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, Benjamin R., and Bradbury Thomas Nelson. 1995. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and inquiry. Psychological Message 118: iii–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Azmat J., Tazeen Southward. Ali, and Ali Chiliad. Khuwaja. 2009. Domestic violence among Pakistani women: An insight into literature. Isra Medical Journal 1: 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Michael A., Mian Bazle Hossain, Saifuddin Ahmed, and Khorshed Alam Mozumder. 2003. Private and community-level determinants of domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. Census 40: 269–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, Rukhsana, and Ruhi Khalid. 2003. Human relationship between conflict resolution strategies and perceived marital adjustment. Journal of Behavioral Sciences 14: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, Etienne G., James A. Mercy, Linda L. Dahlberg, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. 2002. World Written report on Violence and Wellness. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Langlais, Michael, and Siera Schwanz. 2017. Religiosity and Relationship Quality of Dating Relationships: Examining Relationship Religiosity equally a Mediator. Religions eight: 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Loren. 2005. How Does Organized religion Influence Marriage? Christian, Jewish, Mormon, and Muslim Perspectives. Union Family Review 38: 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Stephen R., Huston Ted L., Johnson Elizabeth One thousand., and Shelley Thou. MacDermid. 2001. Office residual among white married couples. Periodical of Wedlock and Family 63: 1083–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, Ann S., Cutuli J.J., Janette E. Herbers, and Marie-Gabrielle J. Reed. 2009. Resilience in Evolution. In Oxford Library of Psychology. Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Edited past Shane J. Lopez and Charles R. Snyder. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, Mario, and Phillip R. Shaver. 2003. The Attachment Behavioral Arrangement in Adulthood: Activation, Psychodynamics, and Interpersonal Processes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by M. P. Zanna. New York: Elsevier Bookish Printing, vol. 35, pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, Kristin D. 2003a. Evolution and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity two: 223–l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, Kristin D. 2003b. Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy mental attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity 2: 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, Kristin D. 2011. Self-Compassion: Cease Chirapsia Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind. In The Role of Self-Pity in Romantic Relationships. Edited by Kristin. D. Neff and Due south. Natasha Beretvas. New York: Morrow, vol. 12, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, Kristin D., and S. Natasha Beretvas. 2013. The Role of Cocky-pity in Romantic Relationships. Self and Identity 12: 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, kristin D., Ya-ping Hseih, and Kullaya Dejitthirat. 2005. Self-pity, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Cocky and Identity 4: 263–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia, Tjaden, and Thoennes Nancy. 1998. The Prevalence, Incidence and Consequences of Violence against Women: Findings from the National Violence against Women. Survey Written report No: NCJ 172837. Washington, DC: U.Due south. Section of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Perveen, Aisha, and Sadia Malik. 2019. Determinants and Outcomes of Family unit Violence among Married Adults of Punjab: Role of Mediating and Moderating Factors. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Islamic republic of pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Razera, Josiane, Clarisse Mosmann, and Falcke Denise. 2016. The interface betwixt quality and violence in marital relationships. Paidéia Ribeirão Preto 26: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016. The gender pray gap: Wage labor and the religiosity of high-earning women and men. Gender & Social club 30: 643–69. [Google Scholar]

- Scot, M. Allgood, Sharon Harris, Linda Skogrand, and Thomas R. Lee. 2008. Marital Commitment and Religiosity in a Religiously Homogenous Population. Marriage & Family unit Review 45: 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, Laura. 2016. Marital sanctity, relationship maintenance, and marital quality. Periodical of Family unit Issues 37: 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 2002. Physiology and faith: Addressing the "universal" gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Report of Religion 41: 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, Nicholas T., Sean C. Sheppard, John P. Forsyth, and Mitch Earleywine. 2011. Cocky-pity is a ameliorate predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and low. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25: 123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Elizabeth Conway. 2015. Cocky-Pity and Self-Forgiveness as Mediated by Rumination, Shame-Proneness, and Experiential Abstention: Implications for Mental and Concrete Health. Electronic Theses and Dissertations, Paper 2562. Eastward Tennessee Country University, Johnson City, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 1996. Violence against Women. Geneva: WHO Consultation. [Google Scholar]

- Zakar, Rubeena, Muhammad Z. Zakar, Rafael Mikolajczyk, and Alexander Krämer. 2012. Intimate partner violence and its association with women'south reproductive health in Pakistan. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 117: 10–14. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1. A schematic model of religiosity and its moderation between family unit violence and marital quality.

Figure 1. A schematic model of religiosity and its moderation between family violence and marital quality.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the mediating role of cocky-compassion betwixt family unit violence and marital quality.

Effigy 2. Schematic representation of the mediating office of self-compassion between family unit violence and marital quality.

Figure 3. Graphical representation of moderating role of religiosity between family violence and marital quality.

Effigy iii. Graphical representation of moderating function of religiosity betwixt family violence and marital quality.

Effigy 4. Simple arbitration model for family violence study in the form of a statistical diagram. Notes: a is the path A showing the effect of family violence on self-compassion; b is the path B showing the effect of self-compassion on marital quality.

Effigy 4. Elementary mediation model for family unit violence study in the class of a statistical diagram. Notes: a is the path A showing the effect of family unit violence on self-compassion; b is the path B showing the upshot of cocky-pity on marital quality.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients and inter-correlation amidst scales.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients and inter-correlation amid scales.

| No. | Variable | M (SD) | α | S | K | 1 | ii | three | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Family Violence | 91.14 (26.00) | 0.94 | −0.05 | −0.80 | - | −0.08 | −0.40 * | −0.38 * |

| ii. | Self-Compassion | 36.66 (6.42) | 0.71 | −0.54 | 0.19 | - | 0.31 * | 0.41 * | |

| three. | Religiosity | 56.58 (8.10) | 0.75 | −0.20 | −0.x | - | 0.45 * | ||

| iv. | Marital Quality | 127.80 (23.52) | 0.84 | 0.26 | −0.91 | - |

Table ii. Inter-correlation among scales and subscales.

Table ii. Inter-correlation amidst scales and subscales.

| Calibration/Subscale | α | i | 2 | 3 | 4 | v | 6 | 7 | eight | 9 | x | 11 | |

| ane | Family Violence | 0.94 | -- | ||||||||||

| two | Sexual Abuse | 0.81 | 0.84 ** | -- | |||||||||

| 3 | Social dethrone | 0.91 | 0.85 ** | 0.66 ** | -- | ||||||||

| 4 | Economical A | 0.79 | 0.82 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.67 ** | -- | |||||||

| 5 | Psychological T | 0.86 | 0.85 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.60 ** | -- | ||||||

| six | Physical Violence | 0.71 | 0.68 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.57 ** | -- | |||||

| 7 | Marital Quality | 0.84 | −0.38 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.02 | -- | ||||

| 8 | M Aligning | 0.89 | −0.48 ** | −0.xl ** | −0.57 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.08 * | 0.94 ** | -- | |||

| 9 | Yard Satisfaction | 0.73 | −0.16 ** | −0.07 | −0.25 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.06 | 0.86 ** | 0.64 ** | -- | ||

| x | Relation due west/in-laws | 0.seven | −0.18 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.xiv ** | 0.002 | 0.66 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.48 ** | -- | |

| 11 | Self-Compassion | 0.71 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.xvi ** | −0.08 * | −0.08 | 0.17 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.24 ** | -- |

| 12 | Self-Kindness | 0.75 | −0.20 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.09 * | 0.01 | 0.36 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.71 ** |

| thirteen | Self-Judgment | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.fourteen ** | 0.16 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.xviii ** | 0.03 | 0.59 ** |

| xiv | Mutual H | 0.7 | −0.xx ** | −0.17 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.08 * | 0.39 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.74 ** |

| 15 | Isolation | 0.68 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.15 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.01 | 0.09 * | 0.34 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.58 ** |

| xvi | Mindfulness | 0.72 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.10 * | 0.24 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.61 ** |

| 17 | Over-identification | 0.68 | 0.xviii ** | 0.21 ** | 0.fifteen ** | 0.15 ** | 0.07 | 0.25 ** | 0.09 * | 0.05 | 0.12 ** | 0.05 | 0.58 ** |

| xviii | Religiosity | 0.75 | −0.40 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.49 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.forty ** | 0.15 ** | 0.31 ** |

| 19 | Intellect | 0.72 | −0.33 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.l ** | −0.26 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.07 | 0.29 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.02 | 0.xiii ** |

| twenty | Credo | 0.79 | −0.32 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.30 ** |

| 21 | Public Practice | 0.76 | −0.15 ** | −0.09 * | −0.18 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.05 | −0.thirteen ** | 0.22 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.05 | 0.18 ** |

| 22 | Private Practice | 0.7 | −0.28 ** | −0.xix ** | −0.34 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.25 ** |

| 23 | Religious Feel | 0.75 | −0.29 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.thirty ** | −0.20 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.09 * | 0.37 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.xix ** | 0.26 ** |

| Scale/Subscale | 12 | 13 | fourteen | 15 | 16 | 17 | eighteen | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | |

| 1 | Family Violence | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Sexual Abuse | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Social degrade | ||||||||||||

| four | Economical A | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Psychological T | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Physical Violence | ||||||||||||

| seven | Marital Quality | ||||||||||||

| 8 | M Adjustment | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Grand Satisfaction | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Relation w/in-laws | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Cocky-Compassion | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Cocky-Kindness | -- | |||||||||||

| 13 | Self-Judgment | 0.32 ** | -- | ||||||||||

| fourteen | Common H | 0.43 ** | 0.32 ** | -- | |||||||||

| xv | Isolation | 0.39 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.26 ** | -- | ||||||||

| xvi | Mindfulness | 0.36 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.30 ** | -- | |||||||

| 17 | Over-identification | 0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.23 ** | -- | ||||||

| 18 | Religiosity | 0.29 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.06 ** | -- | |||||

| 19 | Intellect | 0.xviii ** | 0.09 * | 0.07 | 0.13 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.07 ** | 0.76 ** | -- | ||||

| 20 | Ideology | 0.20 ** | 0.xiv ** | 0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.46 ** | -- | |||

| 21 | Public Practise | 0.23 ** | 0.02 | 0.12 ** | 0.05 ** | 0.23 * | 0.05 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.3 | 0.33 ** | --- | ||

| 22 | Individual Do | 0.24 ** | 0.06 | 0.23 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.43 ** | -- | |

| 23 | Religious Feel | 0.20 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.04 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.33 * | 0.25 ** | 0.37 ** | -- |

Table 3. Moderating function of religiosity between family violence full and marital quality.

Tabular array 3. Moderating office of religiosity between family violence full and marital quality.

| Consequence: Marital Quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | |||

| Model | B | LL | UL |

| (constant) | 129.02 † | 127.23 | 130.81 |

| Family Violence | −0.23 * | −0.29 | −0.16 |

| Religiosity | 1.02 * | 0.80 | i.24 |

| Family Violence 10 Religiosity | 0.01 † | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Low | −0.34 * | −0.45 | −0.24 |

| Medium | −0.23 * | −0.29 | −0.16 |

| High | −0.11 † | −0.20 | −0.02 |

| R two | 0.26 | ||

| F | 69.97 † | ||

| ∆R 2 | 0.01 | ||

| ∆F | 10.45 † | ||

Table four. Model coefficients for self-compassion in relation with family unit violence and marital quality.

Table 4. Model coefficients for self-pity in relation with family violence and marital quality.

| Consequent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G (Self-Compassion) | Y (Marital Quality) | |||||||

| Antecedents | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||

| X (Family Violence) | a | −0.02 | 0.01 | <0.05 | c′ | −0.31 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| M (Self-compassion) | - | - | - | b | 1.42 | 0.13 | <0.001 | |

| abiding | im | 38.43 | 0.95 | <0.001 | iy | 104.51 | v.69 | <0.001 |

| R 2 = 0.01 | R 2 = 0.29 | |||||||

| F (1, 597) = 3.78, p < 0.05 | F (2, 596) = 122.46. p < 0.001 | |||||||

| ab (Indirect effect) = 0.03, <0.001 (BootLLCI = −0.05, BootULCI = −0.001) | ||||||||

| C (total issue) = −0.34 (LLCI = −0.41, LLCI = −0.27) | ||||||||

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of variance for gender differences.

Tabular array 5. Multivariate analysis of variance for gender differences.

| Source | Dependent Variable | SS | df | MS | F | p | η 2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Religiosity | 554.29 | 1 | 554.29 | 8.57 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.83 |

| Marital Quality | 16,323.73 | i | 16,323.73 | 30.99 | 0.001 | 0.15 | 1.00 | |

| Self-compassion | 21.31 | one | 21.31 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.11 | |

| Family unit Violence | 68,441.43 | one | 68,441.43 | 121.41 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 1.00 | |

| Fault | Religiosity | 38,627.12 | 597 | 64.70 | ||||

| Marital Quality | 314,373.42 | 597 | 526.59 | |||||

| Self-pity | 24,665.37 | 597 | 41.32 | |||||

| Family unit Violence | 336,541.21 | 597 | 563.72 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This commodity is an open up admission article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC Past) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/9/470/htm

Post a Comment for "How Social Suport in Pakistani Families Impact Attachemnt of Couples"